Children Love Each Other

What Would My Grandmother Say?

Dear Friends,

For nearly three decades my work has centered around delving deeply into two questions: what makes us fertile in every sense of that word and what is at the root of the relentless unleashing of violence within the human family.

I’m often advised to keep those two subjects separate. I can’t do that. For me, those two subjects are inextricably linked. How can we hope to bring more children into the world without contributing in all possible ways toward building a more life-friendly earth-home not just for them, but for all of creation.

I’ve been struggling so much in the past year with my need to show up. To speak up. Witnessing the deepening divides between family members, within my local community and worldwide, seeing how our eroding ability to hear one another hinders any hope of generative conversations; how much of our emotional energy is channeled toward divisions, I kept asking myself: With such a frighteningly escalating level of us versus them ethos that’s been on full display in the last several years, where do I look for help with finding the most healing, most unifying way to show up?

Then the answer rolled in from an unexpected source. My grandmother. Someone I never met and yet she’s someone I’m still getting to know. And as I grow older and my capacity for holding the particular horror of her experience expands, I appreciate her guidance more and more.

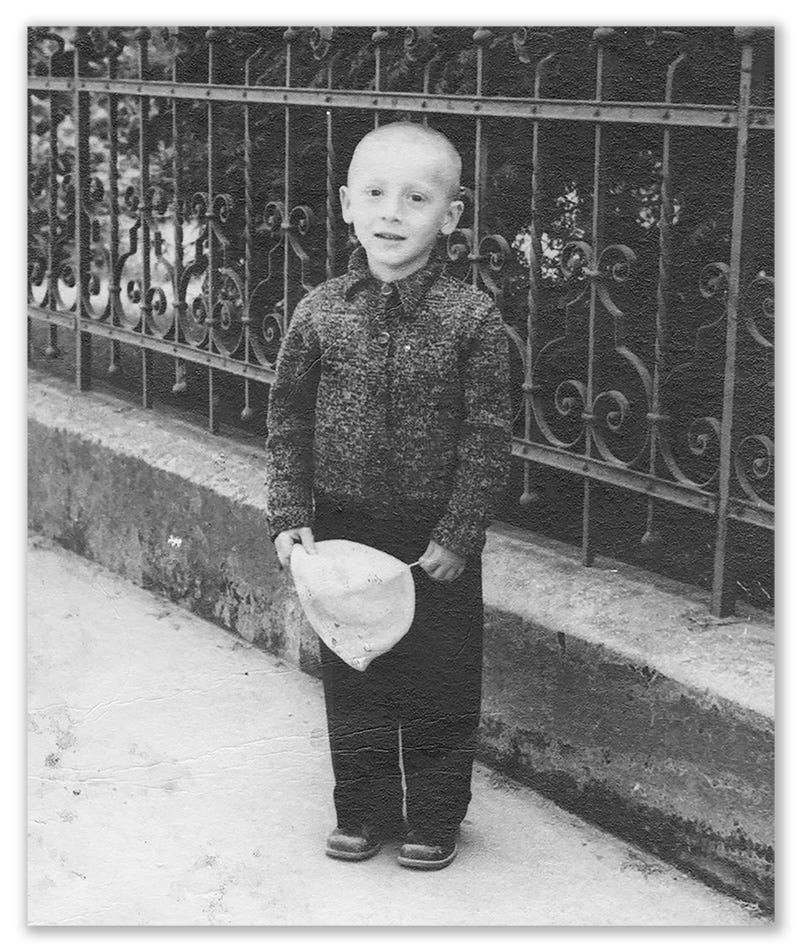

My paternal grandmother, Yolan Klein, was a palpable presence in our childhood home in Eastern Slovakia. In pictures, she was a kind, dignified woman in a silk black dress with a white collar, whose portrait hung over the family bed in our one-room living quarters. My father’s nightly ritual was to stand on tiptoe and touch the glass held by the mahogany frame with his lips. Then he’d invite my sister and me to say goodnight to our grandmother.

(I’m not sure that childhood-trauma therapists of today would approve of this ritual but it’s what my father needed to do for his own healing.)

The Ring and the Note was the story my father told us to explain what gave him the strength to survive starvation, exhaustion, disease, and daily humiliation in Matthausen a death-camp in Upper Austria.

“I kept thinking how it would affect my mother and Adelka, my younger sister, to return come and not find me there,” he said. “I couldn’t do that to them.”

He then described the scene of arriving home after the liberation.

“I walked up three flights of stairs ready to wrap my arms around my mother and sister and found strangers living in our apartment. The neighbor must’ve heard me. She was waiting at the top of the stairwell. Without a word she ushered me into her living room and handed me the possessions my mother thought I would most need when I returned: a winter coat, a down blanket, a ring, and a note. It read:”

‘Children love each other, we will not see one another again.’

Later, my father learned that his mother died in the cattle car on the way to Auschwitz, a death camp in Poland.

In the decades since I heard that story, I’ve pictured my grandmother sitting down to write that note before gathering her belongings for the hellish train ride, choosing the one line that would make a difference in her son’s and daughter’s lives.

“Children love each other.”

My father’s sister, Adelka, didn’t read that note because she and her husband were executed during a massacre six months before the war ended.

My older brother, Robert, didn’t read that note because at the age of eight, he was one of the 1.5 million children murdered in the Shoah.

My uncle Alex, a newlywed didn’t read that note because he was shot trying to escape from a cattle car on the way to Buchenwald.

My cousin didn’t read that note because she didn’t get to be born. When my aunt Magda, shortly before deportation found out that she was newly pregnant, she aborted the cherished baby on the way.

But my father read the note. So did my mother, the woman he married, who survived her young son’s murder and Auschwitz.

My sister and I heard that story and its command many times.

“Children love each other.”

It’s an injunction that continues to haunt me.

Though I strive to do better, love is often not the first response toward my own shortcomings, let alone toward the behavior of many of my human siblings. Still, I trust that the attitude my grandmother asked me to lead with, is always there, buried underneath the resentment, distrust and rage.

Each time I rope off a safe space tor those injured voices within me to speak their truth, I find myself inching just a little closer toward compassion. A little closer to the way I’d like to show up for myself and everyone and everything I’m in relationship with.

I don’t have the answers to solving the escalating horrors of wars or any other high conflicts we humans are attempting to resolve through assaulting one another. I don’t know how I would act or what emotional reactions I’d have to reckon with if it was my son that was abducted, maimed and murdered or if my home was bombed into rubble and my children were dying of starvation.

But if I, someone with food in my pantry and clear skies overhead can’t sit down with my neighbors and hear what pains them, how can I expect people trapped in the war zone to move toward a more peaceful way of treating one another?

My father survived the un-survivable for the sake of the people he loved. Knowing the incalculable cost of violence, the loss of human life, the unfathomable harm to every living thing, what am I, what are you, what are we willing to do for the sake of the children--the people, the world--we claim to love?

Oh Julia, this is my heart's first and authentic reaction. Oh, my heart, would be the second. This ache I feel when I read this or when I remember tragedies of my own family and then my own, every single time my heart breaks a bit. It is so hard sometimes to choose to continue and to choose love - I dont see people who esentually are Love turn into hate or revenge or violence (maybe it happens, I dont see it often), but I do see giving up and losing light, being like a candle without flame. But yes, if we want Love and Life to stay, we need to, each of us, choose every single day to serve Love. For the sake of us, planet and our children. I recently learnt though that protecting our own light is of equal importance as giving it to others - we need to choose our tribe where giving light becomes fire and eventually (hopefully) will be stronger in one moment then darkness. However, if we give a way love to people that are deeply in darkness by making decisions not to serve love, it will weaken love as such and devastates us more. I am still learning this. But I do beleive that tenderness can and will save the world.

You and your message are a gift to us all. I want to engage in those conversations too, to listen, to help you spread this message of love and compassion, profoundly needed in our families and communities. I don't see any other way and I am deeply thankful there are people like you in my life, it makes me feel hopeful, inspired, and motivated.